There’s been lots of talk recently about the quality of private Children’s homes, and some of it is entirely justified. In the last five years, there has been more than a fivefold increase in the number of children placed in homes that were not registered with the regulator. That’s nearly 1,000 children this year subject to provisions that are not just poor, but illegal.

However, it does not follow that all private Children’s homes are a problem. Without them, the system would have collapsed a long time ago.

Anyone who has worked in the sector will recognise the warning signs of a bad provider. I have personally seen questions in WhatsApp groups that ask “do all staff need a DBS?”, “where do you buy uniforms?” and the big giveaway “I am thinking of opening a Children’s home, how much money will I make?” These aren’t the questions of genuine carers, but of people who see care as a commercial opportunity rather than a moral responsibility.

That is not representative of the sector as a whole. There are many private providers out there who have extensive experience managing private Children’s homes and do so with great integrity. They provide loving homes, staffed with people who have spent their lives supporting others, doing the best they can for every young person.

When I entered the sector over forty years ago, the most vulnerable children were often let down not just by society but by the very system intended to protect them. The sector today is far from perfect, but it is almost unrecognisable to the one I joined at 16. Standards are much higher and scrutiny is, rightly, far more intense.

At idem living we make all decisions based on the needs of our young people, and have done so since the very beginning. Even after what felt like a lifetime in the red, we accepted that prioritising the children’s needs meant financial stability would take longer to achieve.

That’s because we see the work we do as a privilege.

It took us 10 years to break even (remember this the next time you see headlines about profit margins in social care). It was then a further 3 years before we provided the first return to shareholders. They patiently waited 13 years to see any kind of return on investment, because they saw the value in sending the children on holidays, building bespoke facilities, and maximising specialist training for staff.

After dedicating our entire careers to social care, the only thing many of us are tired of is being demonised. Those of us in the private sector work intimately with our colleagues in the public sector, collaborating to provide tailored care for every individual. This blended model means that we can provide support where the state struggles.

In a recent report, the National Audit Office highlighted that “in 2022, the Competition & Markets Authority identified that the cost to local authorities of providing their own places is no lower than procuring places from private providers, despite their profit levels” whilst also acknowledging that private providers typically support those with more complex emotional or behavioural needs.

In 2020, Local Authorities directly provided 423 Children’s homes. By 2025, they had increased that number to 483. That’s 60 new homes, or an increase of 14%, in 5 years. Those numbers sound small, but it’s with the context that Local Authority budgets in 2024/25 were estimated to be 10% smaller in real terms than they were in 2010/11. The private sector on the other hand increased their homes from 1,870 to 3,354 over the same time period. That’s 1,484 new homes or an increase of nearly 80%.

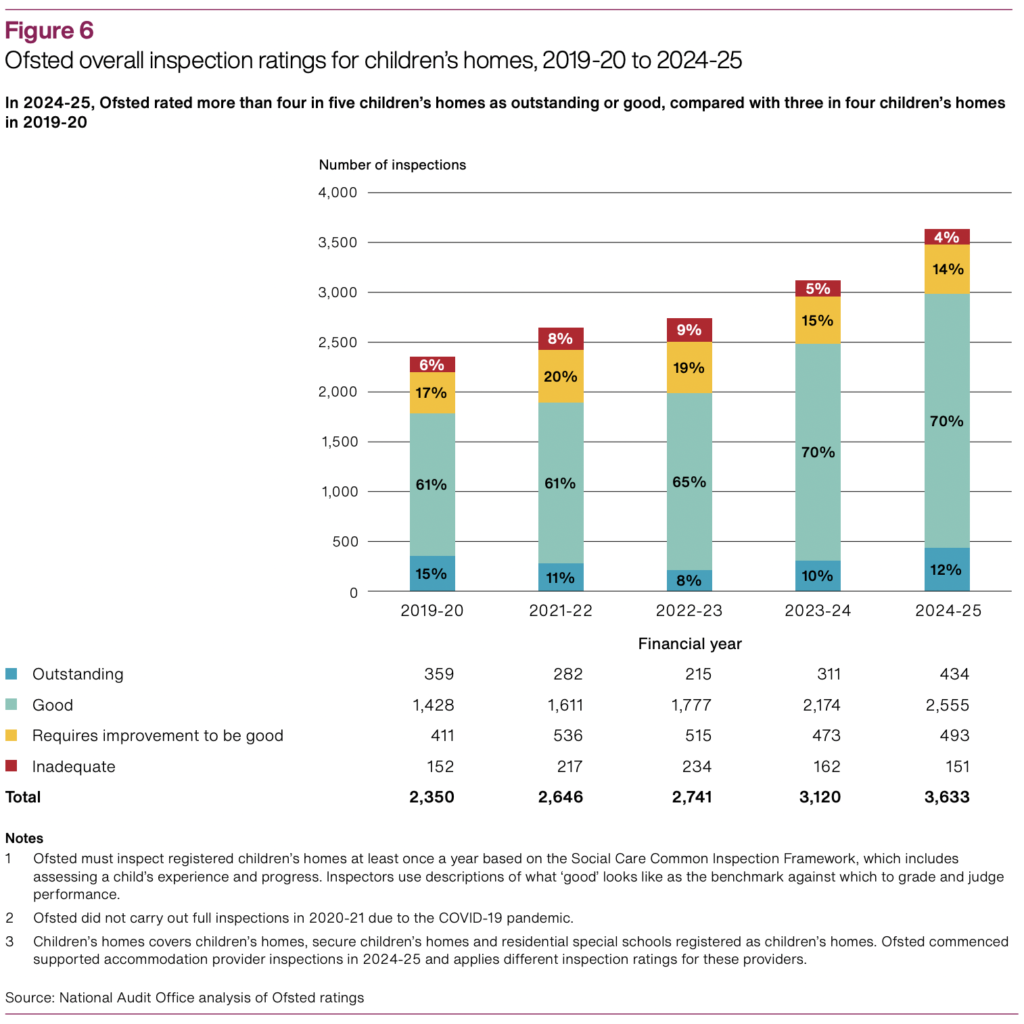

Now it’s true that the private sector provides a larger number of homes rated ‘inadequate’ by Ofsted, but that’s because the private sector provides a larger number of homes. In March 2025, nearly 1.7% of Local Authority homes were rated inadequate, compared to 1% for private homes. Overall, the proportion of homes in the sector rated ‘Good’ or Outstanding’ is growing.

But those are just cold numbers. So let me describe the human element of 1,484 additional private Children’s homes.

Recently, a young person in our care lost a parent in circumstances too awful to describe. As the next of kin, responsibility for planning the funeral fell to them – a devastating task for any family member. But how can we expect a child who has not even reached teenage years to plan, let alone pay, for a funeral?

The Local Authority involved did not want to contribute to the funeral costs, so a Paupers Funeral was planned. I didn’t even realise they still existed! I was told this would not involve a service the young person could attend, and that instead they would receive the ashes afterwards. It was suggested that we might want to plan a private memorial to remember their parent at a later date. I was absolutely horrified.

As a team, we knew this wasn’t right. We agreed it was paramount that the young person could look back in years ahead and feel they did the right thing for their parent.

We decided to organise a full funeral service ourselves, covering all costs, including the cars, the flowers and even the clothes. Our Registered Manager and their team went out of their way, along with the social worker, to plan a truly special day. The Funeral Director was exceptional, as was the Celebrant, who helped us to make arrangements that supported the specific needs of our young person. So impressive are the people in our sector that our young person was joined not just by the IRO and their Responsible Individual, but also by team members that were not even on shift, as well as by one of their teachers.

There was total agreement from our finance team; nobody tried to use a spreadsheet to question whether it was the right thing to do. We even had the flowers sent off after the funeral to be pressed and preserved in frames.

The young person has told me that they want to be a support worker when they grow up, so they can help others the same way we have helped them. That’s better than any judgement Ofsted can give us. I am proud of what we did and what’s more, I know of many other providers who would have done the same. The truth is, we could provide tailored support for that young person, not despite being a private provider, but because we are a private provider.

Yet, being private means people often look at us with distain.

Like everything in life, reality is far more nuanced than it first seems. There are lots of very good private providers, and some particularly bad ones. But I can promise you this, no one is more upset about bad practice than those of us who have spent our careers on the front line.

Don’t judge us all in the same way, and please don’t reduce the complexity of looking after vulnerable children to the simple model of state good, private bad.

Rob Gillespie

Managing Director